This is a book review done backwards. Most people read the book first, then if they’re lucky, they get to meet or even interview the author. I had the fortune of meeting Richard Ford before reading any of his work. I just finished one of his early works, The Sportswriter, which was published to great acclaim in 1986 (which is also the year my novel begins and one reason why I picked up this book).

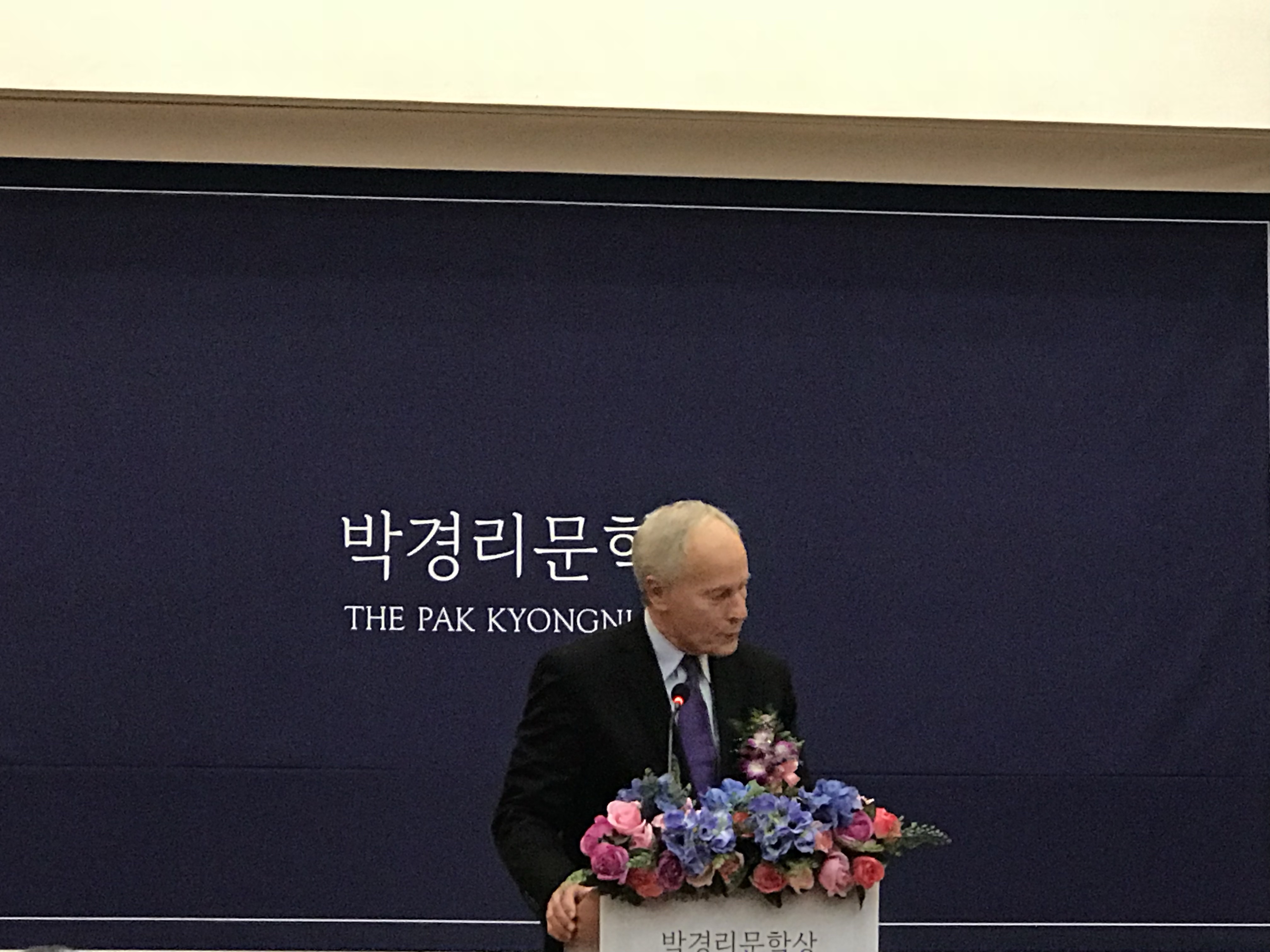

We met at the Toji Cultural Centre last October when he came to receive the Park Kyoung Ni Prize, a decade-long effort by the good folks at Toji and Wonju City/Gangwon province to place the city on the international literary map. While we weren’t privy to the selection process, we did hear that coming to Wonju and attending the Toji Cultural Centre’s annual literature festival was a condition for the prize winner. Watching Ford and his wife at the Centre’s lobby, peering into the rain, mist draping the mountains, I wondered: was this what they had expected? They hadn’t arrived in the best weather: it was damp and cold. Later, I heard they were moving out of the Centre’s accommodations (comfortable, but very simple) to a hotel; Ford said “my wife deserves better.”

That rainy morning, Ford sat down with us (fifteen or so artists, all Korean save for myself and a Spanish playwright) to discuss his writing process and talk about his work. Although there was an interpreter present, some of the discussion, especially about the writing process did not lend itself to easy translation and I found myself an intermediary between Ford and his interpreter.

Anyone can write, Ford told us. He became a successful writer despite his dyslexia. Writing is about the every day, about every day people. As I made my way through The Sportswriter I could see that filtering through: yes, the book is about every day Americans, every day people that someone like Ford would meet. It is entirely appropriate and of his milieu, of his era, including its gender and racial stereotypes. And it is entirely believable that this was normal and acceptable in its time.

Ford made two points about his writing process that I remember clearly, the first being a regular journaling habit. Not journaling in the sense of today I ate ice cream, but writing down lines which came to him, whenever they did. At which point he shared with us a line that had come to him that morning, and all of us ooh-ed and ahh-ed. Ford has a natural gift for sound, putting words together in harmony, something that is obvious from the first page. These words and lines, he says, at some point float its way into a character’s mouth, or becomes a theme, a lodestone for something greater.

The same thought appears almost verbatim in The Sportswriter as Frank Boscombe describes the process of writing a novel, the lines floating around him until the story comes into focus. I can almost imagine Ford himself penning these lines in his pocket notebook, immersing himself in the music of his words until Frank Boscombe congeals, like jelly. Boscombe is described as someone who “likes to see around the edges of his feelings”, who became a sportswriter because he realised he could not, like a true artist, leap off the edge of the known into the unknown. All literature is “the play of light and dark”, and too many aspiring writers forget the word “play”. We were off to a strong start, I thought, speeding through the first third of the book.

Ford’s second point, on fear, arose midway through the seminar when he was asked what drives his writing. “Fear,” he said, which was easy to translate. “About dying. About my wife.” Everyone burst out laughing as I translated the second part of his answer. Ford’s face lost colour. What he had said–and I had interpreted–as masculine joking about fearing one’s wife, really had another meaning: he feared losing his wife, Kristina, whom he has been married to for over 60 years. Confusion explained, mistranslation straightened out, Ford shared with us his devotion to Kristina and the strength their marriage gave him–and how his fear of losing that drives his writing.

I know Ford is not Boscombe, but that anecdote kept coming to mind as I read The Sportswriter. Boscombe has a cavalier attitude towards women, expecting little from them and expecting them to want little from him. Like his relationship with life, he seems to fear engagement–and commitment at a deeper level. And yet women are inexplicably drawn to him. A professor’s wife comes into his office, taking off her leotard and begging Boscombe to have an affair with him. As if to show how much he is ‘above it all’, he walks out without touching her, later walking past her husband the professor with a sneer. He sleeps with eighteen? nineteen? women before his wife has had enough and divorces him. At some point it just became impossible for me to like Frank Boscombe–and even more troubling to discover he was once a much-loved literary character.

At some point in the seminar at Toji, someone asked him about his chances of winning the Nobel Prize for literature. Ford made a wry remark about white, male writers being out of fashion. The hint of loss in his voice gave the lie to the calmness in his eyes. It sounded as though he was ruing the passing of something, the passing of a time–his time–as a white male writer. A time where African Americans barely existed in the consciousness of the average working Joe, the everyday man. They are just negroes who serve the rich white townsfolk in Haddam. Boscombe even has a negro housemate from somewhere in Africa, who seems to flit in and out of the attic he inhabits like a butterfly.

In that moment I was struck with a strange sense of pity: was that what had compelled him to make the long journey (in his seventies, no less) to a town he had probably never heard of, to receive a prize in honour of a writer I’m even more sure he had never heard of prior to winning said prize? I don’t mean to put down anybody at Toji and Wonju, because they are doing wonderful work for writers and artists, but I kept thinking about that comment he made, like coming to South Korea was a consolation prize for not being in contention for the Nobel prize. For being out of fashion in America.

Somewhere at the midpoint, I began to tire of Frank Boscombe’s casualness. There is only so much, I realise, I can take of a character who “sees around the edges of his feelings”. I want to immerse myself in the characters, to lose myself in their world, but I was perpetually viewing them through a cynic’s eye. It felt as though Boscombe was waiting for his great reckoning, that something was going to come and shake him out of his “normal applauseless life” and “psychic detachment”, but when it did hit, nothing happened. Nothing changed. There was no great transformation, no wrestling with his soul.

Perhaps, as Frank Boscombe might say, that is life. But I don’t read a novel because I want to feel the flatness of someone’s emotional life. I want to be taken on a journey, to feel something as I approach its final pages. Perhaps that comes in Independence Day, the sequel to The Sportswriter which won the Pulitzer Prize, but I’m not sure I’ll have the patience for that.

I started googling Richard Ford while writing this review. And to my surprise, I glimpsed a completely different side to the generous, genial teacher we met at the seminar. He apparently has a history of taking criticism badly (this Guardian review also talks about how Ford, born in the deep South before the war, “had to educate himself out of centuries of racial prejudice”), shooting Alice Hoffman’s book when she wrote him a bad review (initiated by Kristina, he says) and blasting Colson Whitehead, an African American writer who gave Ford a negative review in The New York Times. Whitehead’s reaction to his writing, in fact, seems pretty similar to mine:

“Almost every story deals with adultery, invariably in one of two stages: in the final dog days of an affair, or in the aftermath of an affair. The characters are nearly indistinguishable. If I were an epidemiologist, I’d say that some sort of spiritual epidemic had overtaken a segment of our nation’s white middle-class professionals, and has started to afflict white upper-middle-class professionals.”

Perhaps it was a good thing I hadn’t read his work before meeting him. He might not have liked what I have to say.

[…] I watched Parasite, I was reminded of something I wrote a few months ago, a paragraph from Richard Ford’s The Sportswriter, when Frank Boscombe, the […]